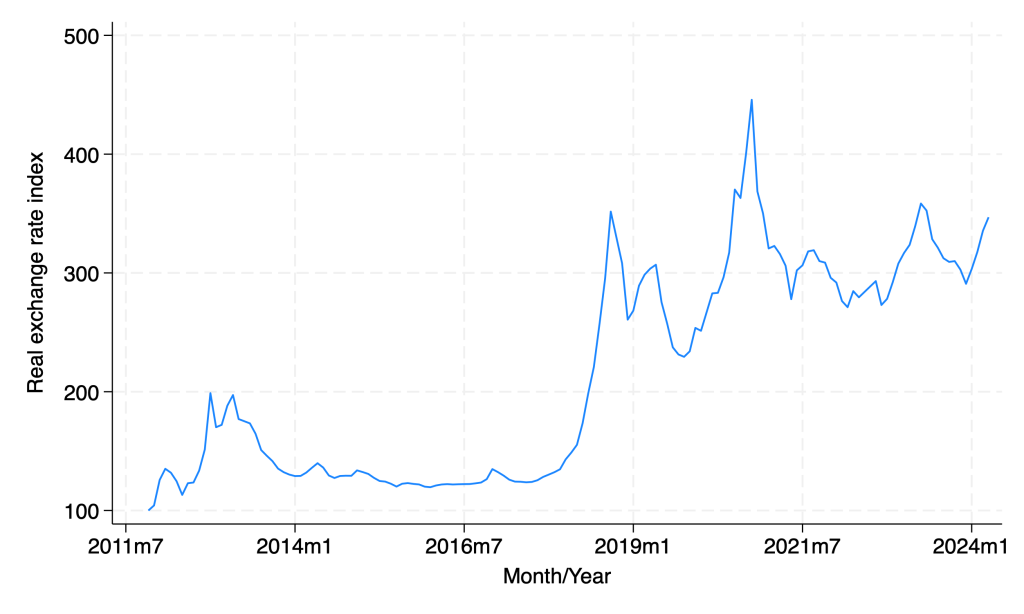

The real depreciation of the rial under sanctions

In my previous post I argued that sanctions and the multiple devaluations they have caused have increased the competitiveness of the Iranian economy. This means that inflation did not increase enough to undo a series of devaluations since 2011, so that the rial is cheaper in real terms, not just nominal terms. If this is the case, removal of financial sanctions confer important benefits on Iran, perhaps exceeding that of the release of frozen funds or more oil sales to China. Below I present the evidence of rial’s devaluation in real terms and leave the question of its potential for growth of non-oil exports to another time.

First, a reminder that real depreciation equals nominal depreciation adjusted by relative inflations rates in Iran and the rest of the world, or nominal depreciation plus foreign inflation rate minus domestic inflation rate. In the case of Iran, since there are several exchange rates, we have to decide which one to use. The free market rate is unofficial but has significant influence on the general price level, the decisions to move capital abroad, and prices of other asset. The official rate is subsidized and used mainly for import of essential goods. The gap between the free market rate and the official rate can be large. Until recently it was nearly ten times the official rate (600,000 rials per USD vs. 42,000 — today it is 392,000 rials). There is at least one other rate that hovers in between and influences prices, the rate that prevails in the organized market between licensed importers and exporters.

In the graph below I calculate the real exchange rate (RER) based on the free market rate, not because most transaction are done at this rate, but because at the margin it has the most influence on domestic prices. RER differs from the real effective exchange rate (REER) in that the latter takes into account the share of other countries in Iran’s foreign trade. The World Bank REER for Iran rose by a factor of 4.1 during 2011-2023, which is more than the increase in the RER I show here, presumably because of added trade protection.

First, notice two effect of two bouts of sanctions, in 2011 and 2018, that cause large nominal devaluations as well as changes in the RER. After 2011, when sanctions tightened first, RER rose but came down a couple of years later as the JCPOA increased oil exports and helped moderate the increase in local prices. In contrast, after 2018 RER stayed high because there was no such respite from oil exports, and prices increased to weaken the rial. In neither case did inflation fully neutralize the effect of devaluation. The RER is now 2.5 times as high as it was in 2017 and 3.5 times as high as 2011. This is a considerable increase in the competitiveness of Iranian workers and their products.

Nominal devaluation does not always mean decline in the real value of a currency. Argentina and Brazil in different times experienced high inflation and real appreciation, that is, their wages and prices increased so fast after devaluation that they wiped out any gains in competitiveness, and even worsened it.

Since Iran has experienced real depreciation as a result of the sanctions, access to global banking can have significant impact on its non-oil exports. The implication is that focus on short term deals with the US for release of frozen funds or allowing China to buy more oil from Iran ignore the larger harm to Iran’s economy from denying it access to other global markets. Taking advantage of the comprehensive caused by real devaluation will benefit growth of output and employment.

To repeat, financial sanctions prevent Iranian products from competing in foreign markets at a time that oil sanctions have reduced the real costs of Iranian labor in terms of foreign currency. Policy analyses that bemoan limits on oil exports and “the loss of value of the national currency” often ignore the more important constraint on non-oil exports that prevents Iranian producers to take advantage of their lower unit labor cost in foreign markets, and the potential for Iran to export its way out of economic malaise if it can reach a deal that allows Iran to re-engage in international trade.

Hi

Please explain where you came to the conclusion in preparing that chart number one; and this phrase:

“after 2018 RER stayed high because there was no such respite from “oil exports and prices increased to weaken the rial”,

and you have considered this phenomenon as a natural reaction of the market (if I understand correctly, comparing the real value of domestic goods compared to world prices), you have not talked and wrote about the general intervention of a non-scientific and non-national orders to reduce the value of the national currency of the governments of the time, and probably You have not taken into account in your assumptions.

If the above statement is correct, then what worries me is that it is a non-scientific and conscious explanation for the devaluation of the national currency in the future. A common phenomenon that causes rent-seeking capital to accumulate wealth from the national wealth of oil or other raw materials for global sale, and on the other hand, creates a miserable life for the country’s working people

And then you came to the strange conclusion that these events, which have caused the misery of people’s lives and labor force, have caused;

“This is a considerable increase in the competitiveness of Iranian workers and their products.”

There seems to be no room in your argument for raising the value of labor against inflation, and instead raising labor productivity and creating internal and national competition to perpetuate the natural decline in the rate of profit.

I’m not an economist, but as an engineer with an interest in political science, I’m surprised by your arguments.

Parviz

If you could, please write your expaltion in Farsi language.

A personal observation:

I was in Iran in April 2019. The rate of exchange in the free market was 13000 tomans to the dollar. It is roughly 60,000 today- a 4.6 times increase in the exchange rate in five years.

During the same period, using an average yearly inflation rate of 40%, the prices have risen about 5.4 times. Inflation has outpaced currency devaluation.

Kaveh Mirani