Iran’s recent economic growth explained in four graphs

This post is a brief look at the latest national accounts data and what they say about Iran’s economy in recent years. The evidence is somewhat puzzling: there is economic growth, albeit slow, while net investment is heading to zero!

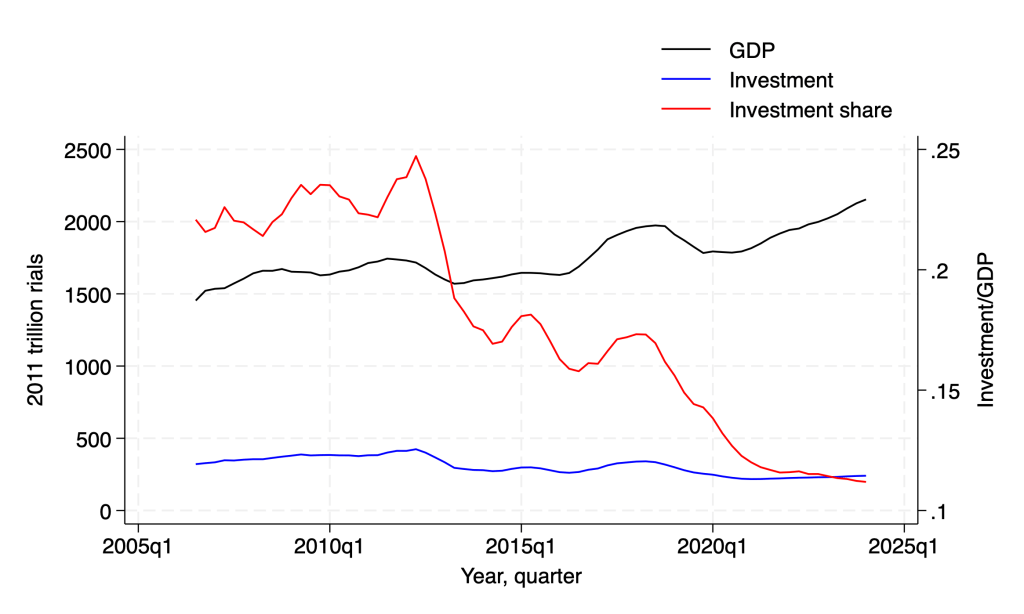

Let’s start with the expenditure side of the national accounts, which best illustrates this puzzle. As you can see in Figure 1 below, in the past decade GDP has been growing slowly with some ups and downs as sanctions tightened (2011), eased (2016), and tightened again (2018). During this time, however, the share of investment in GDP fell drastically, also varying closely with the ups and downs of sanctions.

It is fair to say that sanctions have failed to reach their objectives, as our recent book argues, because the economy has not collapsed (even slowly growing) and because Iran has not softened its position vis-a-vis US and Israel. But sanctions have been effective in severely hurting investment (green line in Figure 1). The large drops in the share of investment coincide with the timing of Obama sanctions starting in 2011 and Trump sanctions in 2018.

Whereas the GDP was able to grow after Trump’s trashing of the 2015 nuclear deal (in 2023 growth reached 5.7%), investment continued to decline, reaching a historic low of 11% as share of GDP in 2023. This is well below what the country needs to keep its existing stock of capital in good repair, suggesting that the positive GDP growth is being financed in part by eating into the capital stock. If so, even the 4-5% growth rate of the past few years will not endure.

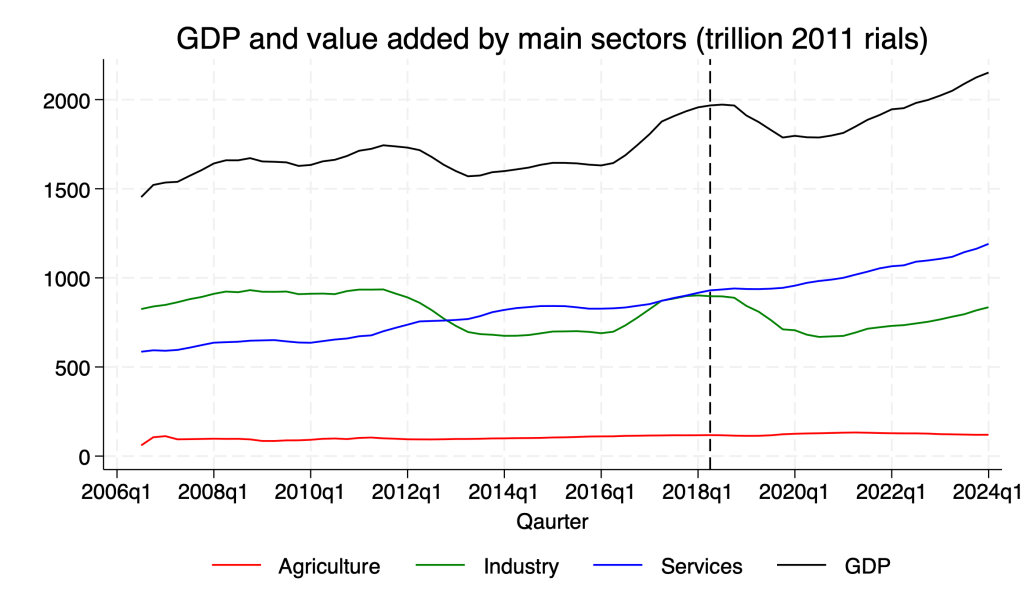

Next, let us view in Figure 2 the GDP trend from the perspective of its main sectors. This graph reveals the weak base of the recent economic growth in Iran, mainly coming from services, which produces many low productivity jobs. Agriculture appears in decline (more evidence of this from employment in Figure 4), and industry has had a mixed record, falling rapidly and recovering slowly.

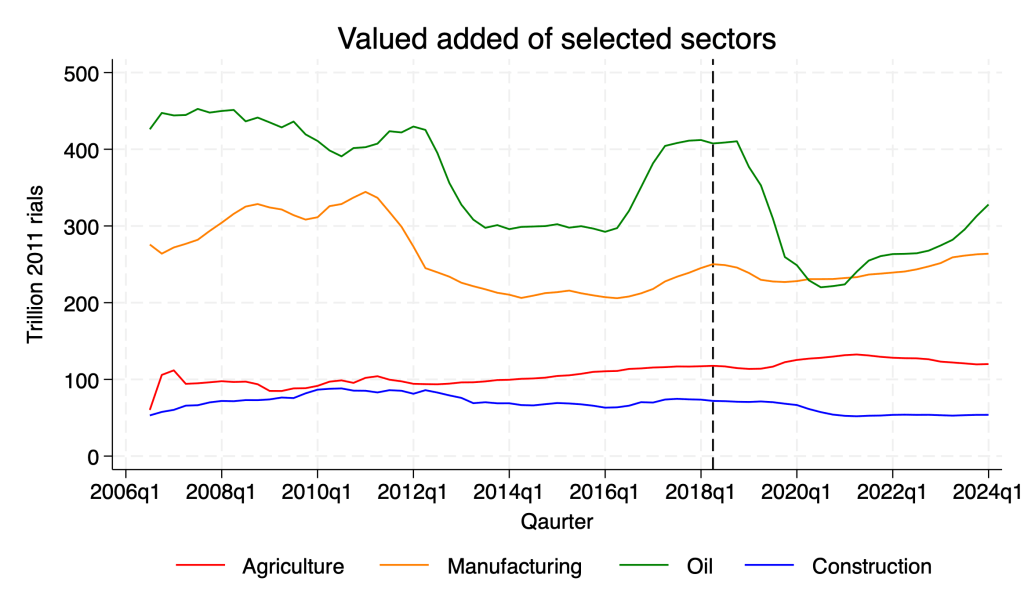

Industry combines two sectors with very different roles in the economy, manufacturing, and oil and gas. It is good to view these sectors individually. In Figure 3 we see that the sharpest impact of Trump’s maximum pressure campaign has been on Iran’s oil and gas sector. Oil exports were hit hard in 2018, which sent shock waves throughout the economy. Manufacturing was the next hardest hit, because it uses imported capital goods and intermediate products, whose prices rose as the currency depreciated.

Despite continued limits on oil exports imposed by US sanctions, value added in oil and gas has recovered better than manufacturing (or construction for that matter). This is in part because of Biden’s relaxed enforcement of Iran’s oil sales to China, as common wisdom goes, which will likely end if Trump is elected. It is also because of rising domestic consumption of energy, driven by extremely low domestic prices.

What is happening to agriculture is even more sad and concerning. Agriculture’s troubles are not closely connected with sanctions (it was doing ok during 2011-2018). Most likely its decline after 2018 is the result of the decade-long drought, related to climate change (though agriculture, too, uses imported inputs which Trump sanctions may have hit). The effect of climate change is exacerbated by low energy prices, which have encouraged excessive use of water pumps running on cheap diesel and electricity and depleting underground aquifers commonly owned by this and future generations.

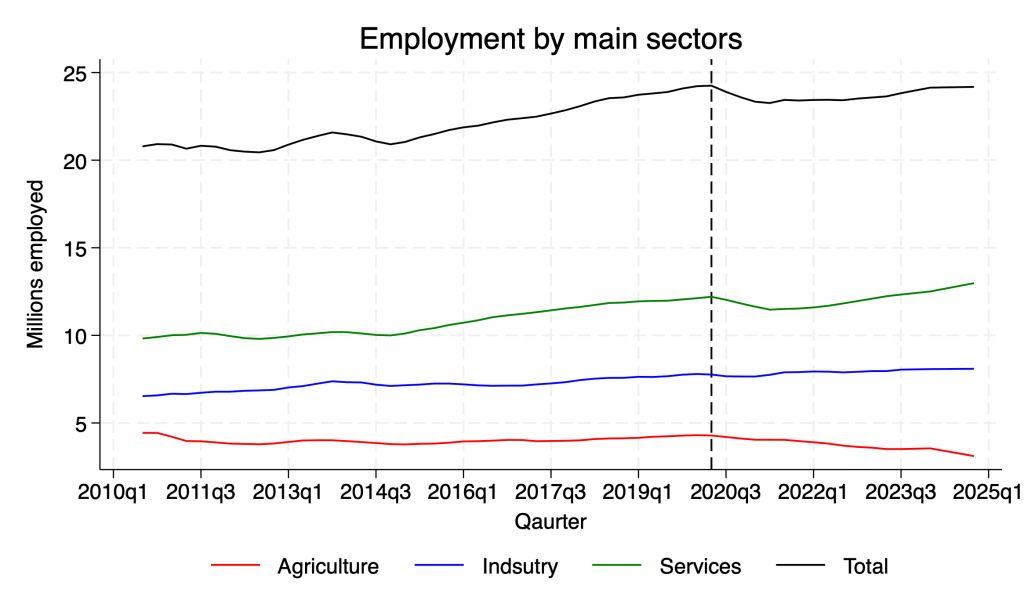

The troubles brewing in Iran’s rural areas is more clearly seen in employment trends, depicted in Figure 4. Employment in agriculture fell from 4.3 million in 2019 to 3.5 million in 2023. Covid’s impact is also most obvious here, in total employment, which has not fully recovered to its 2018 level. The culprits here are employment in services, which was most hurt by Covid, and agriculture, which is suffering from the drought.

Can these trends be turned around? Not easily if sanctions continue. But investment and manufacturing will respond quickly to lower pressure from sanctions. More oil exports and foreign exchange earnings will help manufacturing producers buy new capital and intermediate goods from abroad, expanding their output and employment.

Equally important, if not more so, is the removal of financial sanctions. Deep real devaluation has significantly reduced Iranian labor costs in foreign currency terms. Removing the banking restrictions on Iranians’ ability to move money around globally will cut the cost of non-oil exports, allowing Iran’s newfound competitiveness to conquer a few export markets. Removing banking sanctions are harder to remove than for oil, but if I were Iran I would put access to financial markets ahead of selling more oil. While earning foreign exchange, manufacturing and service exports create more jobs than oil and oil-based petrochemicals that are currently generating the bulk of Iran’s hard currency earnings.

[…] US sanctions and heightened regional tensions. Investment in Iran has fallen to a historic low of 11% of GDP; a deteriorating electricity and natural-gas network (once a source of pride) has led to more […]

Thanks Djavad jan. It’s easier just to respond to your email rather than remember login details! Doesn’t the apparent paradox (high growth accompanied by low capacity building) simply reflect recovery from Covid with unutilized capacity?

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

Thanks for the observation, Hossein jan. Yes, recovery from Covid is a good explanation for the growth. But it does not explain the falling trend in investment’s share, so my fears for weak growth in the next few years remain — unless a serious inflow of resources not only reverses this trend but compensates for lost investment in the past decade.