Iran’s currency crisis: what the rial does (and does not) tell us

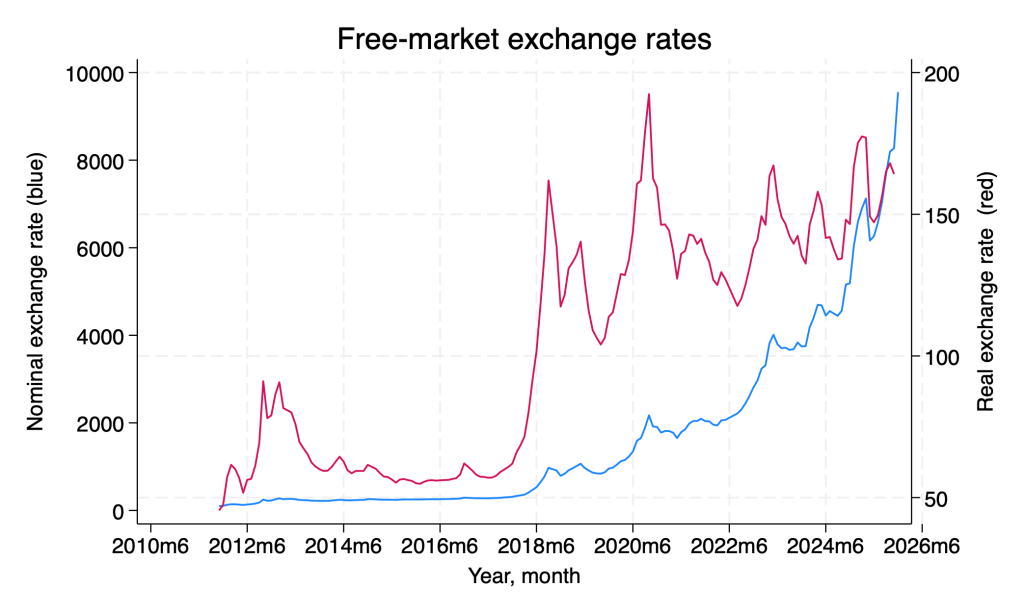

The recent nationwide protests in Iran are the result of an accumulation of grievances, increasingly focused on what is commonly described as the “loss of value of the national currency.” This phrase is a familiar everyday lament among Iranians, who often equate the value of the rial—measured in U.S. dollars—with living standards. In doing so, they typically focus on the free-market exchange rate. Although this is a narrow market, it produces the most dramatic signal. The bulk of foreign exchange transactions take place at lower rates, but access to them is limited. The free-market rate, now around 1.3 million rials per dollar and averaging just under one million in the past month (see the blue line in Figure 1, left axis), is roughly 100 times its level when Obama-era sanctions took effect in late 2011.

The depreciation of the rial is closely associated with inflation. On the one hand, because most domestically produced goods have an imported component, their prices rise when the currency depreciates. On the other hand, inflation itself undermines the value of the rial. There is no reason, however, for domestic prices and the exchange rate to move in perfect tandem. Devaluation can outpace inflation if demand for dollars rises faster than demand for the rial, as it has in Iran over the past decade and a half. This is shown by the near doubling since 2011 of the real exchange rate (RER) — which corrects the nominal exchange rate by the difference in the rates of inflation in Iran and the US.

The RER is a more meaningful economic indicator than the nominal exchange rate because it measures the competitiveness of Iranian products in global markets—or, more accurately, would measure it, since U.S. sanctions prevent Iran from competing globally. The near doubling of the real exchange rate since 2011 is enormous by historical standards and reflects Iran’s potential competitive advantage. This is one reason I have argued that financial sanctions do more harm than oil sanctions. For those who earn income abroad and spend it in Iran, the country appears cheap, allowing them to feel relatively wealthy and to enjoy inexpensive restaurants or low-cost services such as dental care. For those who live and work in Iran, however, currency depreciation is bad news: it can push many consumer goods out of reach, with notable exceptions such as bread, gasoline, and public transportation.

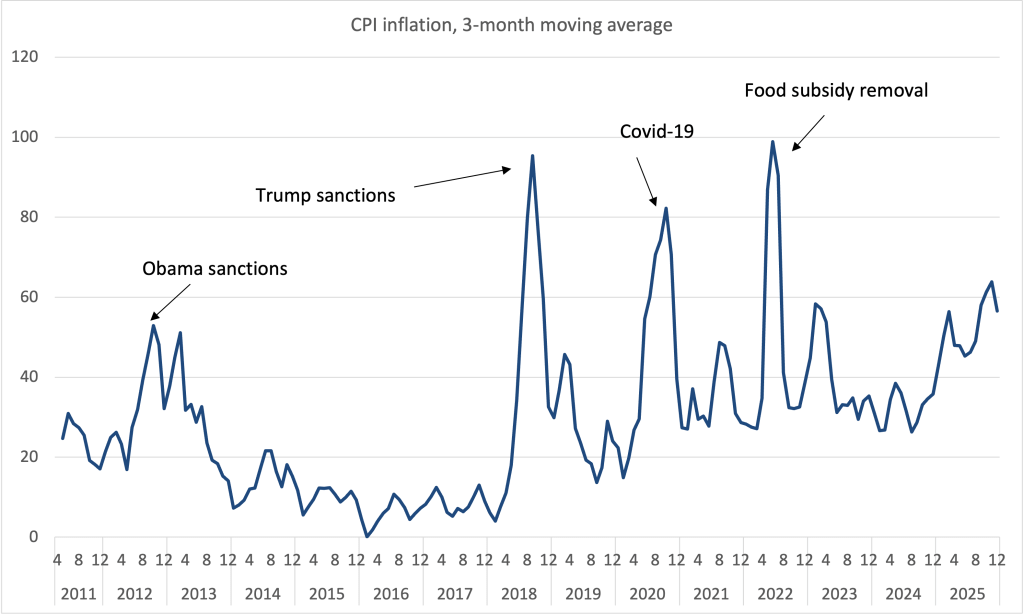

As Figure 2 shows, inflation has risen sharply following each major collapse in the value of the rial, surging after the Obama and Trump sanctions in 2012 and 2018. The figure also illustrates the close association between depreciation and inflation. This is hardly surprising. As noted earlier, most locally produced goods contain imported inputs, causing prices to rise when the currency weakens, while inflation itself erodes the value of the rial. There is no reason for prices and the exchange rate to move one-for-one, and devaluation can exceed inflation when demand for dollars increases more rapidly than demand for the domestic currency.

It is therefore unsurprising that news of currency reforms that are certain to devalue the rial was quickly interpreted as signaling further declines in living standards, regardless of how the government intended to use the proceeds. The government has announced plans to substantially increase cash transfers, which could raise the real incomes of the poor, as a similar policy did in 2022 under the Raisi administration.

Opposition to the reforms that may have triggered the initial protests in late December, as some have claimed, was partly rooted in the historical association between devaluation and inflation. However, if the new transfers resemble those implemented in 2011 under Ahmadinejad and again in 2022 under Raisi, fears that inflation and currency depreciation automatically translate into impoverishment may not be realized—at least for households below the median income. For decline in poverty after these reforms, see here and here.

In economics, currency depreciation is not inherently good or bad. Even when it is harmful, it does not necessarily signal economic collapse. Western media outlets that favor the forcible replacement of the Islamic Republic with a U.S.-friendly (read docile) regime invoke the specter of imminent collapse to discredit diplomacy. Years ago, The Atlantic described the sharp devaluation following the tightening of Obama-era sanctions in 2011 as evidence of a dying economy. Nearly 15 years later the economy is suffering but it is still alive. Thanks to cash transfers and subsidies, people can at least afford to buy their daily bread, children go to school, and buses run.

PS. I have corrected the definition of RER in the initial text to read “[RER] corrects the nominal exchange rate by the difference in the rates of inflation in Iran and the US.” (1/7/2026)

By the way, whatever is the economics, it is very unlikely that the Iranian government can come back from this brutal crackdown on protesters and killing of hundreds. Socially this government will be dealing with internal and external backlash of that and won’t be a normal government in relation to its relation with its population. The politics is going to be overtaking the economics for foreseeable future. The country is entering a revolutionary phase.

Many basic needs of purple are imported, from gas to food. With Iranian government oil revenue under pressure, they lack the means to import as much as they used to.

That is the real driver of these reforms. It is not possible to import these any more at the same level. And they cannot easily be replace by internally produced products.

As a result it is going to be the case that the total consumption by people on Iran needs to drop significantly.

The direct subsidized might maintain the consumption by the poorest percentiles, but that just means the reduction in consumption will be more by middle class.

The consumption by the top percentile (the rich as they call it in Iran) is not elastic to these changes, despite governments attempts to frame this as curbing of the inappropriate consumption by the rich.

So the impact will be felt as a significant reduction of quality of life for the middle class. This is going to be the case in the short term. And for the longer term impact to be avoided, you need adoption of the consumption, e.g. reduction in heating/cooling of houses by better isolation, public transport instead of taxis and cars, … and those need investment which is unlikely to happen. So the reduction of the quality of life for the middle class might not be just a short term impact of these policies.

A good graph to look at is the purchasing power real income in dollar terms adjusted for inflation, whether mean or median family. By my calculations, it peaked at the end of Khatami’s second term and Ahmadinejad’s first term (both because of reforms during Khatami and high oil prices). Since sanctions, it has dropped by 75% and that is what people feel as reduction in quality of life. And with these reforms, it will drop further. The direct subsidies will not be covering the increase in the prices. The reforms are good policy from economic perspective and necessary and unavailable, but it will have a significant negative real impact on the quality of life for the middle class.

What are the units of numbers in the top graph? You mention the free-market rate is now around 1.3 million rials per dollar, but the graph goes up to 10,000. Same question about the red curve.