Sanctions and unequal regional growth in Iran

Regional equity is crucial in a centralized yet multi-ethnic country like Iran. In the language of empirical growth literature, convergence allows poorer regions to catch up, moving the country toward a more balanced standard of living. This process strengthens national unity by ensuring that no region is left behind. In contrast, divergent growth, where disparities widen over time, risks pulling regions apart and undermining national cohesion.

Globally, economic divergence between rich and poor nations has been a major concern among development economists, with many studies showing that global income gaps have widened in recent decades. While such disparities do not pose an existential threat to the global economy or political order, they can become intolerable within a single nation, where people share a government and a common national identity.

In this post, I examine how Iran’s provinces performed in terms of income growth before and after the imposition of comprehensive international sanctions in 2011. Using data on per capita real expenditures—a proxy for living standards—from the Household Expenditure and Income Survey (HEIS) of the Statistical Center of Iran, I compare provincial growth rates in two periods: 1990–2010 (the two decades following the Iran-Iraq war and before comprehensive sanctions) and 2011–2023 (the sanctions years).

Sanctions on Iran became serious and far-reaching after 2011, expanding beyond restrictions on specific international transactions to broader financial controls. With the loss of access to the global banking system, nearly all international transactions became difficult, significantly affecting economic activity.

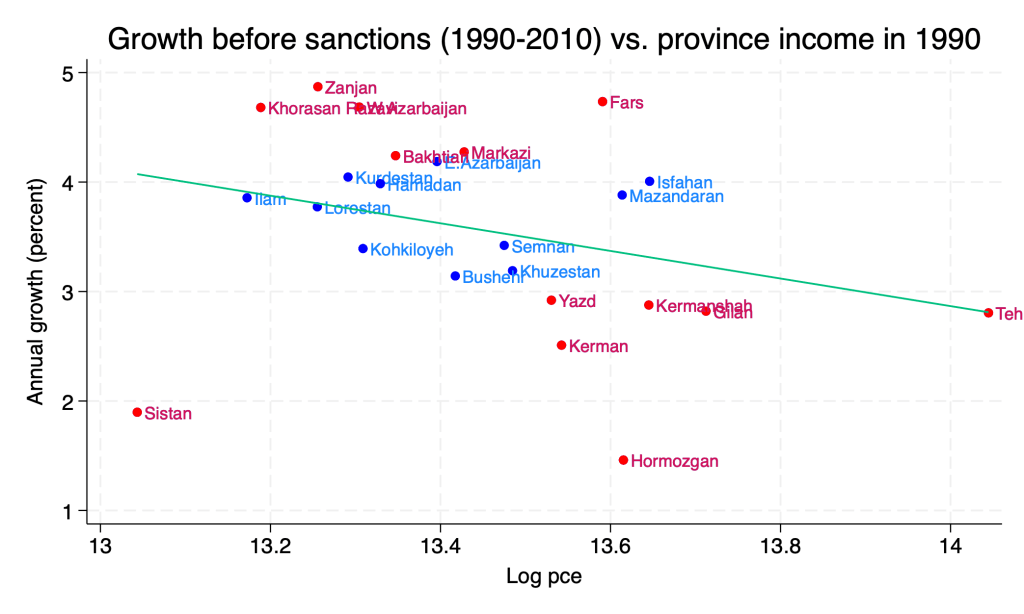

To assess whether richer provinces had an advantage in either period, I regress the average growth rate for each period on the log of expenditures at the start of that period. (Growth rates are calculated as the difference between the log of expenditures at the end and the beginning of the period, divided by the number of years.)

The first graph shows each province’s position in a diagram of growth (vertical axis) versus log per capita expenditures (horizontal axis) in 1990. The downward-sloping fitted line indicates convergence, meaning that incomes in poorer provinces grew faster. The best and worst performers are shown in red; others are in blue.

This is good news for regional equity: provinces like Zanjan, Khorasan Razavi, and West Azerbaijan, which were at the poorer end in 1990, in the next 20 years grew faster than average—4.9%, 4.7%, and 4.7% per year, respectively, compared to the national average of 3.6%. However, Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran’s least advantaged province, grew by less than 2% per year, far below the average—no convergence there.

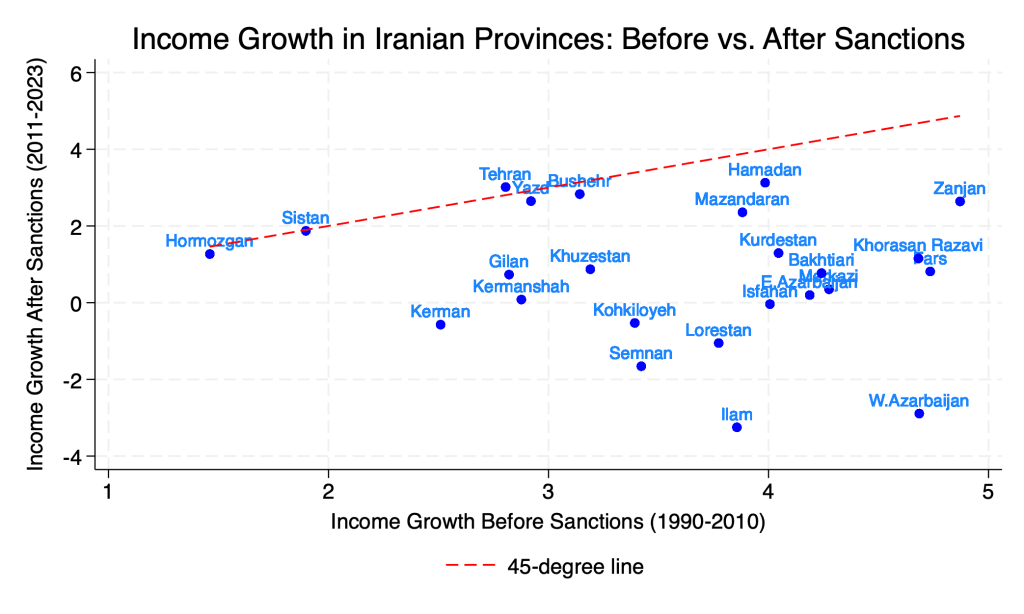

The second figure shows the same relationship for the post-sanctions period (2011–2023). All growth rates are lower, though there is considerable variation: Alborz grew by 4% per year, while Ilam shrank by -3.5% annually. The fitted line is nearly flat, indicating no clear evidence of convergence in this period. (The slope estimate is not statistically significant.)

A final graph compares provincial performance across the two periods. The horizontal axis shows growth before sanctions (1990–2010), averaging 3.6% per year, and the vertical axis growth after sanctions, averaging just 0.7%. The 45-degree line indicate which provinces performed the same in the two periods (none did better under sanctions). Most lie below the line, meaning they did worse under sanctions, as expected.

Sistan and Baluchistan again stands out. It had the lowest level of expenditures at the start of both periods (1990 and 2011), but its growth rate remained almost unchanged between the two periods. It lies on the 45-degree line, along with provinces like Bushehr, Hormozgan, Tehran, and Yazd—indicating their economies were least affected by sanctions.

In contrast, the western provinces of Ilam and West Azerbaijan are farthest from the 45-degree line. Both performed well before sanctions, with growth rates of 3.9% and 4.9%, respectively, but suffered sharp declines after 2011 (-3.2% and -2.9%). These provinces appear to have been among the most adversely affected by sanctions.

West Azarbayjan is an interesting yet sad case. Lake Urmia went dried up so as to foster agricultural growth. Yet the result is -3% growth!

I wish a more detailed analysis of each provonce or type of province could be presented. For industrial province Markazi with so much air pollution the growth rate is also sad.